Tijuana Bibles & The Perverted Savants Club

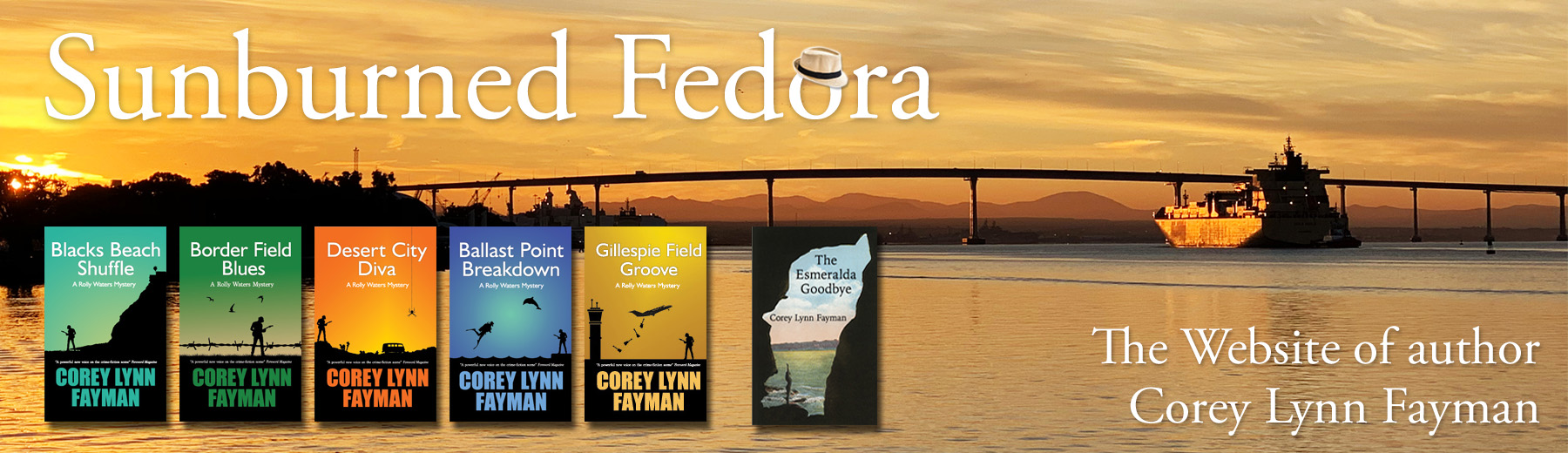

My recent novel, The Esmeralda Goodbye, is set in Southern California in the mid-1950s. Some of the characters I developed early on were a trio of disaffected young teenagers—Danny Stirling, Willie Denton, and Rachel Shapiro—who chafe against the conventions of high school and the provincial attitudes of their hometown. They’re smart, talented kids, but they’re seen as troublemakers and weirdos by their teachers and fellow students.

Danny, the ringleader, embraces his outsider status and flaunts his rebellious attitude. He convinces the other two to join him in a secret club, The Perverted Savants. The objective of the club is to share information about all the things polite society doesn’t want them to know—sex, crime, politics and adult hypocrisy.

To give the story verisimilitude, I needed to find examples of transgressive literature and art of the time, but also something the kids would have access to and could believably share with each other at their meetings. Danny, the reader, brings in a paperback copy of Jim Thompson’s 1952 noir, The Killer Inside Me. Rachel, whose father is a scientist, brings in her parents’ copies of the Kinsey Reports. Willie is a talented artist who likes to draw cartoons, which made me think of the underground comics of the 1960s (Zap Comix, Robert Crumb, et al), but my story preceded those publications by at least ten years. MAD magazine had been around for a couple of years by the time of my story, but I wanted something more salacious. What kind of cartoons could Willie have brought to the meetings?

That’s how I learned about Tijuana Bibles.

Tijuana Bibles weren’t from Tijuana. And they weren’t bibles. They were pocket-sized pornographic magazines, published in the United States from the 1920s to the early 1960s. Most of them were eight-page comic strips printed in black and white. At least a couple of panels in each magazine featured the characters engaged in some form of explicit sexual activity.

Some of the characters were original creations, but many of the booklets featured parodies of celebrities or well-known cartoon characters.

Even Mickey Mouse got in on the act.

These were major copyright infringements, of course, but the nature of the medium, the anonymity of the artists and the lack of publishing information helped protect the creators from legal entanglements. The booklets were sold under the counter at magazine stands, bus terminals, penny arcades, and second-hand bookshops. Downtown San Diego in the 1950s was a popular gathering place for US Navy sailors and shops like those were plentiful in Horton Plaza and the Gaslamp District. Tijuana Bibles were almost certainly sold in some of those shops, so it was feasible that my characters might get hold of a copy.

In today’s one-click-away hardcore world, the Tijuana Bibles seem almost quaint. They’re funny and feisty and, in their way, provide a snapshot of American sexual attitudes in the 1950s, an underground challenge to the prevailing puritanism of the day.

If you’re interested in learning more (or want to see more explicit images from the comics than I’ve provided here), you may want to check out Tijuana Bibles:Art and Wit in America’s Forbidden Funnies by Bob Adelman and Richard Merkin. For more more about the history of Tijuana Bibles, try Wikipedia.